There are many qualities we consider when deciding whether or not to accept submitted manuscripts for publication. (Read all about the fate of manuscripts rejected from Anaesthesia here.) Obvious items include originality, quality, clinical applicability, and for clinical trials, the prospective trial registration status….but more on that later. This month in Anaesthesia, Athanassoglou et al. employ a systematic review to ask whether or not there is evidence on which to base the practice of anaesthetic throat pack insertion. The striking finding is that all the evidence is of harm, with no apparent benefits associated with the use of anaesthetic throat packs. The authors, together with the National bodies DAS, BAOMS and ENT-UK, devised an evidence-based consensus statement recommending the routine use of throat packs inserted after induction by anaesthetists should be abandoned (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Consensus protocols for throat pack use. There is no indication for the routine insertion of a throat pack by an anaesthetist at or after induction or tracheal intubation in upper airway surgery. The protocol to be followed depends on whether it is judged best for the surgeon to site the pack (as when the pack will be within the operative field), or for the anaesthetist to site the pack (as when the pack is outside the operative field). (*The anaesthetist may be asked to assist, for example, with laryngoscopy; **notwithstanding cases where the jaw is wired, patient transferred ventilated to intensive care, etc, or where a pack is intentionally left in‐situ).

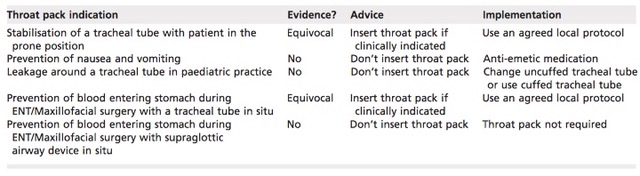

Have we therefore reached the end for throat packs inserted by anaesthetists? Craig Bailey et al. argue the new practice recommendations, as they stand, do not address all the pertinent issues. Advice is offered in light these new recommendations for five common anaesthetic throat pack indications and anaesthetic departments may wish to incorporate this into any new throat pack protocols (Table 1).

Table 1 Indications for throat packs and the advice of Bailey et al.

Does surgery and anaesthesia affect cognition in adults without existing cognitive dysfunction? This observational study finds an association between surgery, the number of operations and longer cumulative operations with a decline in immediate memory. The declines were small but significant, and the rate of deterioration was greater in those with lower performance at enrolment. Despite these seemingly striking results, it is probably too early to recommend any changes to clinical practice regarding the prevention, diagnosis, management and prognosis of cognitive changes after surgery. This paper is, nonetheless, essential reading for all anaesthetists.

Imagine a journal receives a randomised controlled trial reporting on an area important to patients and clinicians, funded through charitable donations and/or taxes, and with important scientific conclusions. The authors, however, did not register their trial prospectively through a recognised registry. Should such papers be rejected automatically or dealt with in a flexible and pragmatic manner? El-Boghdadly et al. present the findings from their study into adherence to guidance on the registration of randomised controlled trials published in Anaesthesia. They conclude that, though generally encouraged as good practice, trial registration was not associated with the acceptance of manuscripts submitted to Anaesthesia or subsequent citation metrics. In their editorial, Pandit and Klein discuss the many reasons for this editorial policy and call for the consideration of other options, such as the automatic upload of all trial protocols, correspondence and associated documents by the ethics committees granting approvals. They question whether or not automatic rejection of unregistered prospective research is itself ethical, as patients have already been subjected to the intervention in an ethically approved manner. On the other hand, Smith and Dworkin argue trial registration is the best method currently available to verify whether articles are reporting results from pre-specified hypothesis and methods, and to address concerns about selective reporting, falsely positive results and selective publication. What do you think? Who wins the argument? Join in the discussion either on Twitter or through our correspondence website.

The Difficult Airway Society recently issued new guidelines for airway management in critical ill adults. In their editorial, Professors Pandit and Irwin discuss the implications of these new recommendations for anaesthetic departments. It seems the way we think about an airway with predicted difficulty in critical illness needs to change. For example, appropriate assistance should be available from the start, rather than when problems arise later on. ‘Fast track’ extubation following airway difficulty is generally inappropriate, and planned extubations should only be attempted during daytime hours. The question is, can our hospitals adapt to these guidelines, which will no doubt improve patient safety?

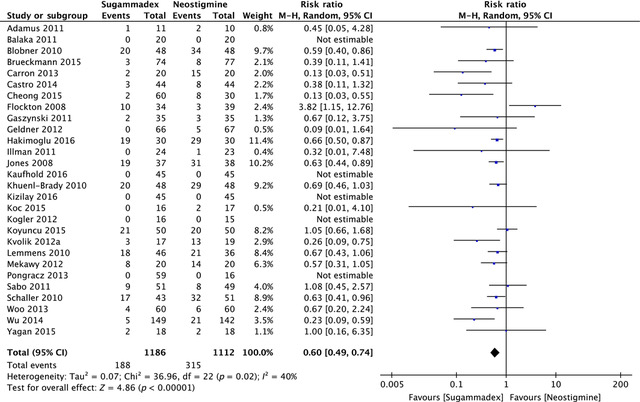

We have seen several recent papers comparing the efficacy and safety of sugammadex as compared with neostigmine for the reversal of neuromuscular blockade. (For an excellent up-to-date clinical summary of sugammadex, including when we should consider using it, check out this editorial.) This month, a Cochrane systematic review concludes that sugammadex works far more quickly than neostigmine and is associated with fewer adverse events (Figure 2). Some may argue, however, that we will only be able to fully appraise the safety of sugammadex when its use becomes more widespread, at least in the UK.

Figure 2 Forest plot of risk of adverse events; sugammadex (any dose) vs. neostigmine (any dose). M‐H, Mantel‐Haenszel.

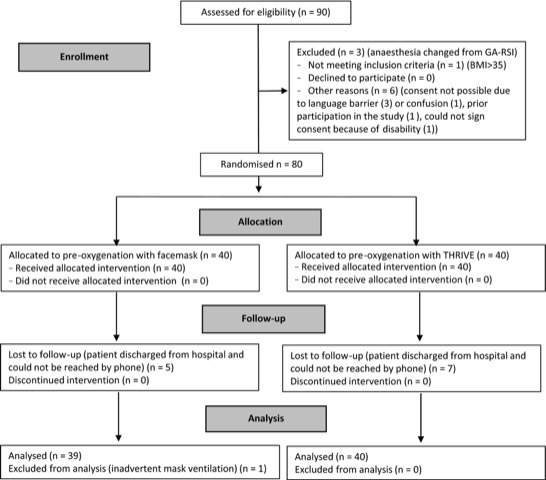

Does transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE) prevent hypoxia when apnoea is prolonged due to difficulty with intubation for rapid sequence induction in adults? (Read the landmark THRIVE paper by Patel and Nouraei from 2015 here!) This randomised controlled trial in 79 patients, where THRIVE was compared with facemask pre-oxygenation, seems to suggest so (Figure 3). THRIVE may therefore provide continuous oxygenation rather than just pre-oxygenation and be useful for rapid sequence inductions.

Figure 3 CONSORT diagram. THRIVE, transnasal humidified rapid‐insufflation ventilatory exchange; GA, general anaesthesia; RSI, rapid sequence induction; BMI, body mass index.

In this month’s ‘statistically speaking’, Choi et al. ask questions of before-and-after studies in relation to an article previously published in March by Ångerman et al. Of course, randomised controlled trials are not always feasible nor ethical, but before-and-after studies introduce sources of bias such as changes in patient characteristics, treatments and medications, lack of blinding during data collection and the continuous gradual improvements in the standard of care. Despite these and other limitations, there is no-doubt that before-and-after studies can be informative and useful. Maybe we should always view data collected today as potentially controlling for trials conducted in the future?

Anaemia is common before cardiac surgery in the UK and is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality in such patients. This retrospective observational study finds that the WHO definition for anaemia significantly underestimates the number of women at increased risk of morbidity associated with anaemia before cardiac surgery (Figure 4). Would women benefit from a threshold of anaemia set to Hb < 130 g.l-1? There is clearly a need for a well-designed prospective study. (Read all about the controversy around diagnostic criteria for preoperative anaemia in women here.)

Figure 4 Relationship between pre‐operative Hb level and postoperative length of stay in women (white circles) and men (black diamonds). Hb, haemoglobin; LOS, length of stay.

Elsewhere this month there is a narrative review of the anomalies with target-controlled infusions (a must read for TIVA enthusiasts!), a simulation study of the effect of palpable vs. impalpable cricothyroid membranes in an emergency front-of-neck access scenario, an assessment of the tolerability of the Cook Staged Extubation Wire in patients with known or suspected difficult airways extubated in intensive care and a randomised controlled trial of the ilioinguinal–transversus abdominis plane nerve block for elective caesarean section.

Our most discussed article from the April issue was this case-series of general anaesthesia-free major breast surgery by Pawa et al. Does the choice of anaesthesia matter for such patients? This secondary analysis of patients enrolled in an ongoing clinical trial seems to suggest so, as it concludes that propofol-paraverterbral anaesthesia attenuates the postoperative increase in neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, a potentially important marker of inflammation and immunosuppression.

Finally, applications are invited for a 1-year Fellowship attached to the journal, starting at the AAGBI Annual Congress in September 2018. The deadline for applications is 31st May 2018 and all the information on how to apply can be found here. We hope you enjoy the May issue of Anaesthesia as much as we did and, as always, we look forward to discussing each article with you and receiving your feedback on Twitter.

Mike Charlesworth Andrew Klein

Trainee Fellow Editor-in-Chief